Lucky Strike ($LUCK): Stable Demand, Fragile Credit

Understanding the capital structure beneath Lucky Strike's diversification story

🚨 Connect: Twitter | Threads | Instagram | Reddit | YouTube

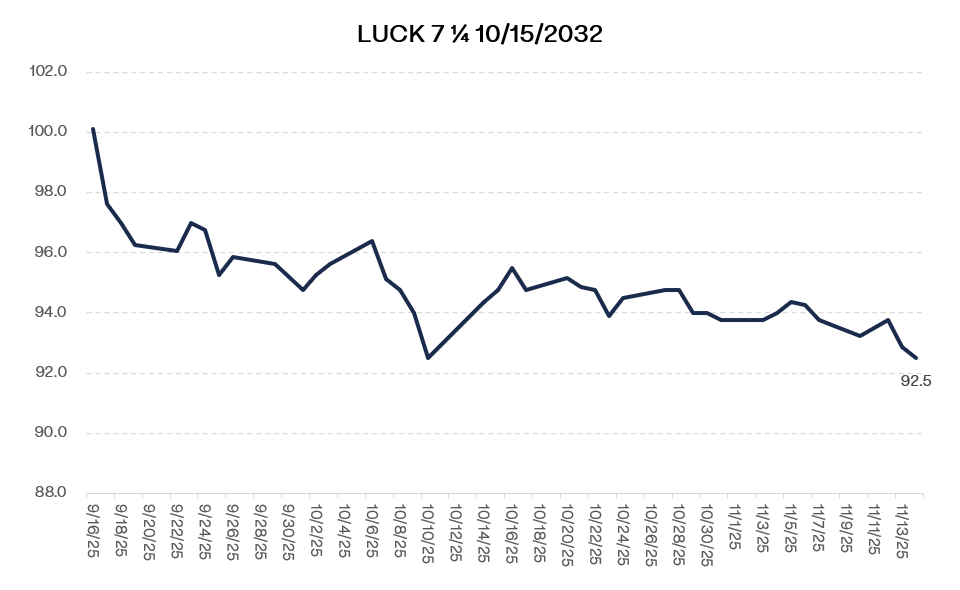

The bonds trade at 93.

Everyone’s acting like this is some boring, defensive consumer credit. “Recession-proof” bowling. Sticky customer base. No maturity wall. Just collect your 7.25% coupon and don’t overthink it.

Except it’s not that simple.

This is a bowling roll-up that bought cheap alleys, slapped LEDs on the lanes, called it a “premium experiential entertainment platform,” and convinced Wall Street they were building the next Topgolf. Then they went public via SPAC in 2021 because that’s what you did in 2021. Changed the name from Bowlero to Lucky Strike. Changed the ticker from BOWL to LUCK. Rebranding as strategy.

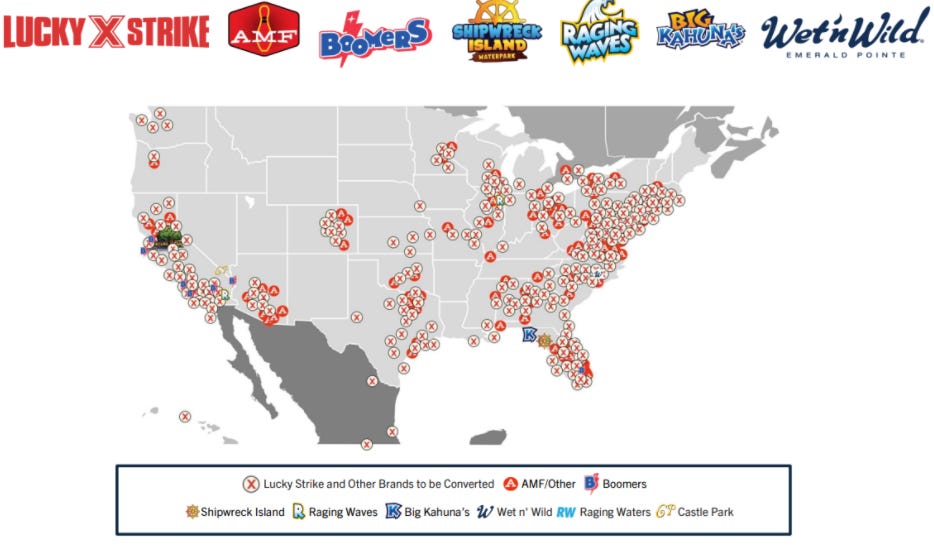

Then they expanded into water parks. Added massive seasonal volatility to a business that was at least somewhat predictable.

The corporate events business? Quiet for now. Tech layoffs killed it. Management keeps saying it’s “normalizing.” Sure.

And they’re still paying dividends.

In truth, bowling kind of works. The category is fine. Retail traffic is actually holding up. Leagues are growing. Food attachment is real. None of that is the problem.

The problem is the structure. What you’re actually underwriting when you buy these bonds. Whether 8.5% YTW is enough for what’s underneath.

Let’s walk through it.

Situation Overview

Bowlero spent the better part of a decade buying up cheap bowling alleys and running them through a standardized playbook. The acquisition pipeline was deep, pricing was attractive, and demand for accessible entertainment stayed consistent. It worked. In 2021 the company went public through a SPAC, which brought in capital but also created new expectations. Management needed to show growth and deliver shareholder returns, so they kept buying back stock and paying dividends even as FCF stayed tight.

That pressure helped drive what came next. The company expanded beyond bowling into water parks, family entertainment centers (FECs), and an upgraded hospitality concept under the Lucky Strike brand. The strategy made sense on paper: broaden the revenue base, increase food and beverage’s contribution, smooth out seasonality, and move upmarket. It’s the same direction everyone else in the space is heading. But what actually emerged is a business with more complexity, more seasonality, and higher capital needs than the original bowling-focused model.

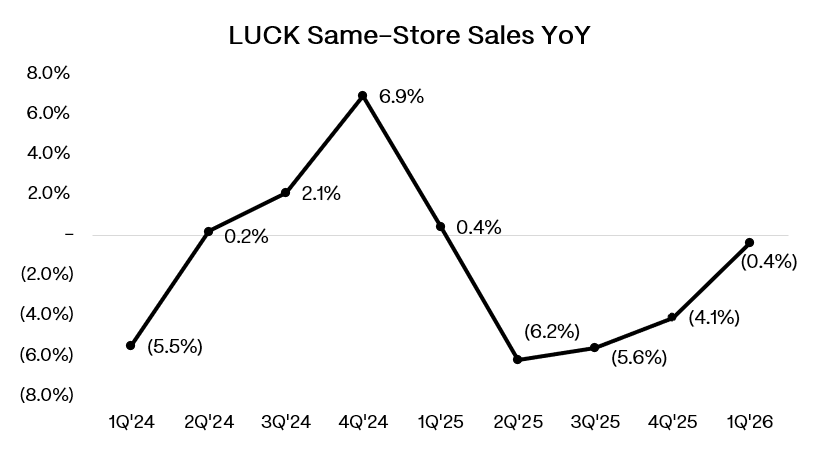

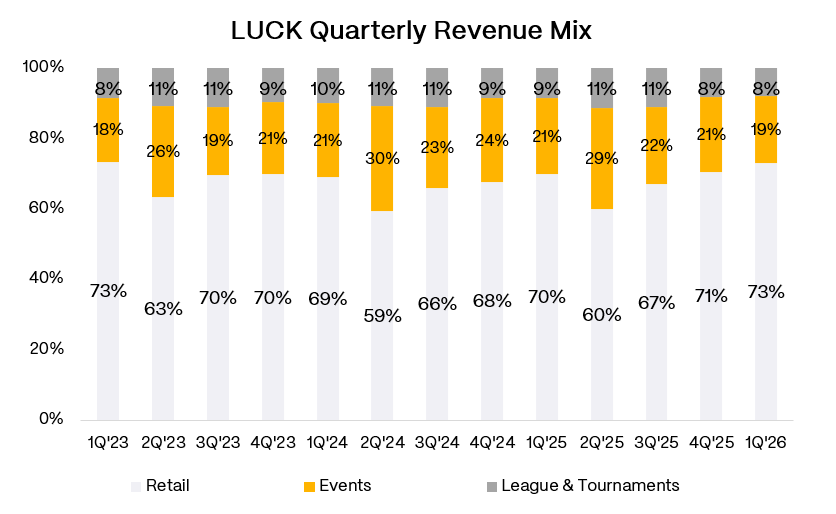

Last quarter captures both the promise and the problem. Revenue was up 12% and EBITDA grew 15%, which looks solid until you check same-store sales. Nearly all of that weakness came from California and Washington, where tech layoffs and corporate budget cuts hammered corporate events. So this isn’t a system-wide demand issue. It’s concentrated in one high-margin segment that used to be a growth driver.

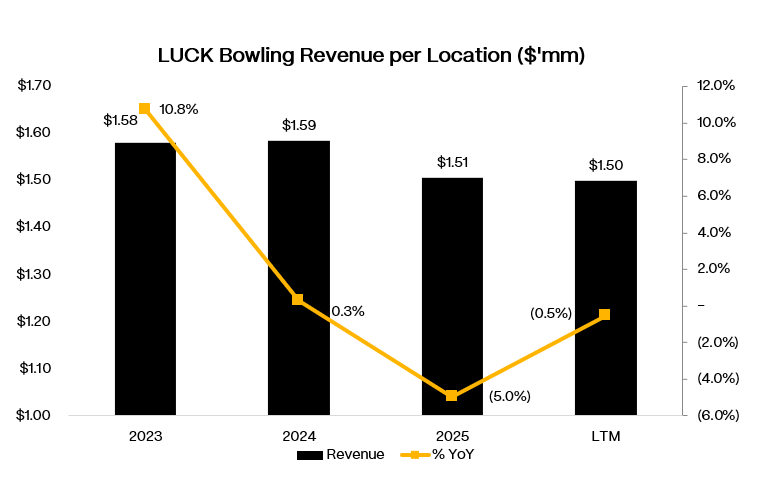

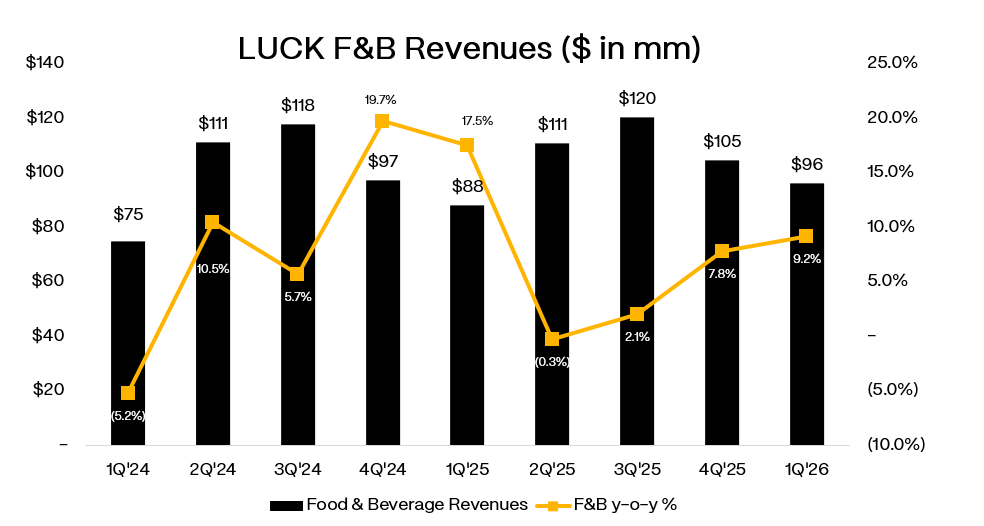

What’s filling the gap tells you where the business is really heading. Bowling revenue per location has been drifting lower for a while now. Events are still below 2023 levels. Most of the incremental revenue is coming from food and beverage instead.

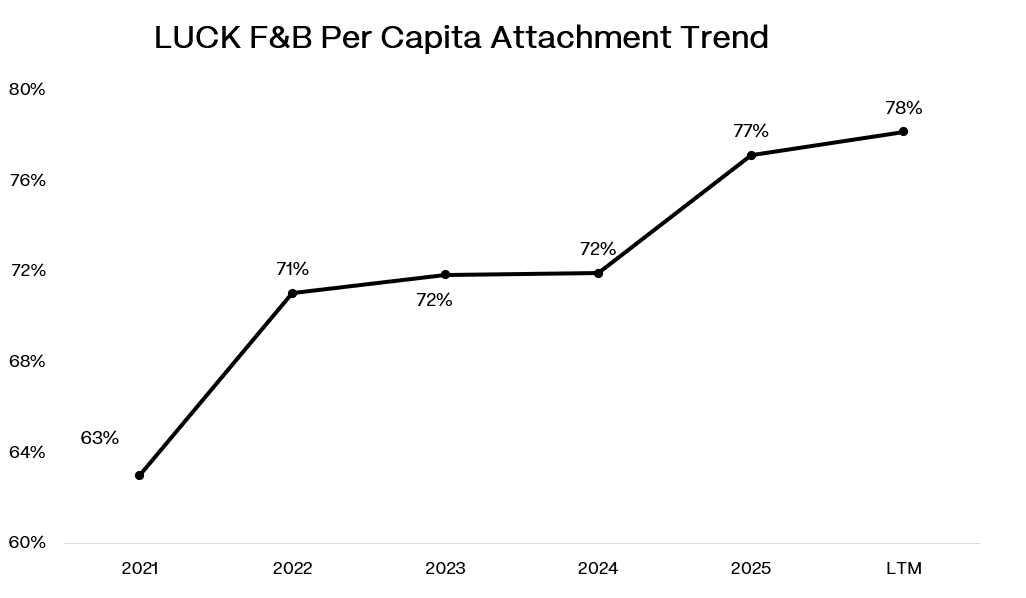

F&B was up 9% with no pricing, which means the entire lift came from higher attachment. That’s fine in the near term, but F&B carries lower margins than events or even bowling, so the mix shift creates its own problems.

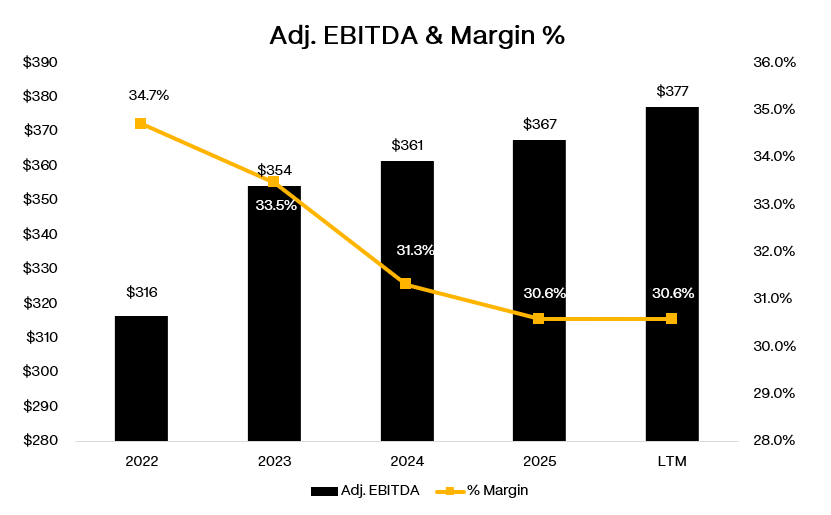

You can see that pressure show up in the margin profile. EBITDA margins have compressed from the mid-30% range down to the low-30s over the last few years. Operating costs are higher, and the shift toward F&B has reduced flow-through on incremental revenue. The latest quarter showed some improvement, but the longer trend is still moving in the wrong direction.

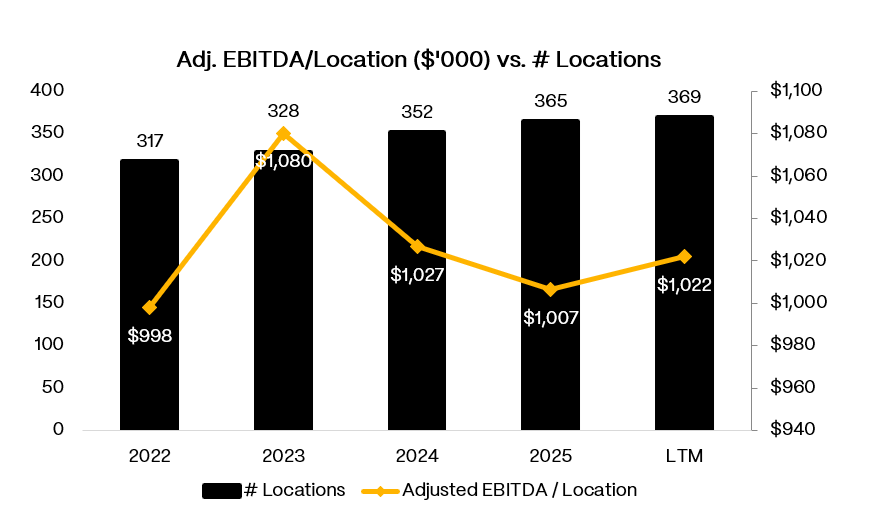

Consolidated EBITDA looks steadier at first glance, but dig into the driver and it’s not organic improvement. It’s footprint expansion. Every period with meaningful EBITDA growth lines up with periods where the company added locations. When location count is flat, EBITDA stalls. That’s a roll-up pattern, not a compounding one, and it explains why management kept pushing forward with acquisitions even after the margin pressure started showing up.

Which brings us to the capital structure. Lucky Strike refinanced its debt and issued 7.25% bonds due 2032 in September 2025. The bonds priced at par and have since traded down to around 93. Around the same time, the company spent $306 million buying the real estate under 58 centers and roughly $90 million acquiring two water parks and three FECs. The real estate purchase makes strategic sense in the long run because it creates future flexibility, but in the short term it just converts rent into finance lease expense without reducing the fixed burden.

The seasonal assets are even trickier. They contribute meaningful EBITDA during summer months but run below breakeven most of the year, which makes the overall business more seasonal without lowering the fixed charges it has to carry year-round.

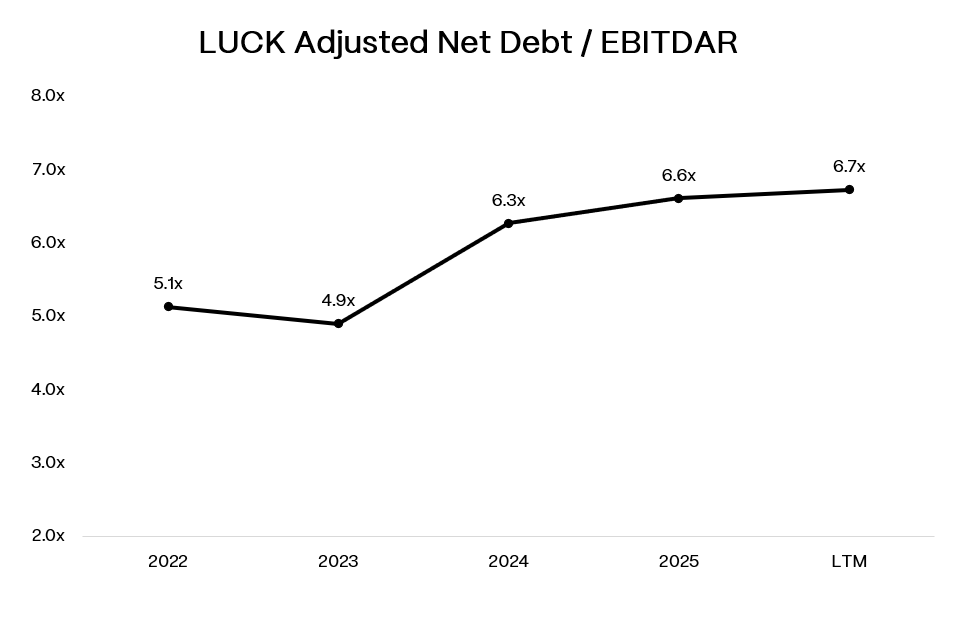

That dynamic shows up clearly in the leverage numbers. Lease-adjusted leverage has been stuck over 6.0x for years with no structural improvement.

The platform produces revenue, but it doesn’t generate enough FCF after rent, interest, and maintenance capex to bring leverage down. And maintenance capex is the part that doesn’t show up cleanly in EBITDA but matters a lot for understanding what cash is actually available.

Bowling centers need constant upkeep. Lanes, pinsetters, amusement games, HVAC systems, and scoring equipment all require ongoing investment. Water parks need repairs, resurfacing, ride maintenance, and safety-related work. FECs need new games, redemption systems, and regular fixes. True maintenance capex likely runs close to $100 million annually, and rebrands (see below) add to that figure. Once you layer in rent and interest expense, there’s not much left over.

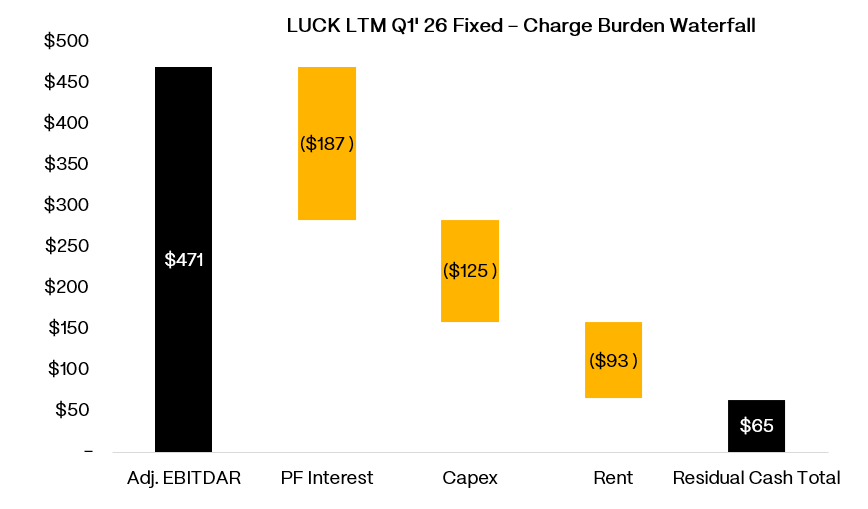

A basic waterfall from EBITDA through those fixed charges shows how tight coverage actually is. Fixed-charge coverage sits somewhere between 1.0x and 1.2x depending on the quarter, which leaves almost no room to handle volatility without tapping debt, leases, or asset sales.

So what you end up with is a business that functions but offers minimal cushion. Demand is stable. Retail and leagues are holding. Food attachment is strong. Water parks add seasonal upside when it matters. But the structure underneath is narrow. The platform needs multiple segments performing at the same time, and the capital structure leaves very little room for things to go wrong in any one of them. LUCK isn’t about to imminently collapse. But the business that looks diversified on the surface, operates like a roll-up with constrained FCF underneath, and that distinction matters more the longer leverage stays elevated.

Here’s what this all means for bondholders and how to play the situation: